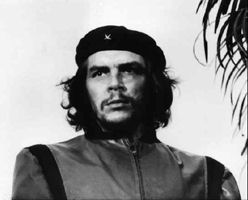

Heroic military figures offer insights into the nature of charisma. Che Guevara stands alongside such earlier leaders as Alexander, Napoleon, Nelson, and more recently, Nelson Mandela. But what do we mean by the charismatic leader?

There will be world-wide acknowledgement this week of the impact of the life and death of Che Guevara, forty years after his execution in the hands of the Bolivian army [on October 9th 1967]. The term most widely used of the Argentine-born revolutionary leader is charismatic.

Guevara’s military efforts were intertwined with those of his close ally Fidel Castro, and it could be argued that in some ways Che ‘out-charismad’ the Cuban.

Fidel became a political leader, preoccupied with the governance of Cuba. That earned him mega-credibility (and to his enemies status as dictator) as the founder and leader of a Marxist state within a hundred miles of the mainland of The United States of America.

In terms of practical consequence, Fidel’s revolutionary efforts had far greater impact than those of Guevara. He led the successful revolution against the Batista regime. Cuba was to become the cockpit of the cold-war confrontation between America and Russia.

In crude military terms, Guevara was more an example of the romantic and tragic figure fighting for a cause against all odds. Military defeat can sometimes become cultural victory, and that happened in spades to Che’s reputation.

Myth-making trumps historical strong suits

The process of myth-making can be seen in the semi-biographical film account of the young man’s South American journey of exploration by motor-bike. In the movie, Che was portrayed, according to one critic, as a Christ-like figure moving among the masses awaiting his emancipatory intervention. The approach, it has to be conceeded, is no more than the customary Hollywood treatment (albeit by a Brazilian director) accorded to heroic figures.

Other critics of Che have highlighted events glossed over in the myth-making process, pointing out that after the successful Cuban revolution, Castro had appointed him a special prosecutor, a role he undertook energetically, at a time when hundreds of opponents of the new regime were executed.

Paul Berman, author of Terror and Liberalism offers one of the most vehement iconoclastic critiques:

The cult of Ernesto Che Guevara is an episode in the moral callousness of our time. Che was a totalitarian. He achieved nothing but disaster. Many of the early leaders of the Cuban Revolution favored a democratic or democratic-socialist direction for the new Cuba. But Che was a mainstay of the hardline pro-Soviet faction, and his faction won. Che presided over the Cuban Revolution’s first firing squads. He founded Cuba’s “labor camp” system—the system that was eventually employed to incarcerate gays, dissidents, and AIDS victims. To get himself killed, and to get a lot of other people killed, was central to Che’s imagination.

The comments following Berman’s analysis put to shame the standard of discussion prompted by almost any web-site I have caught up with. They go a long way to teasing out the ways in which cultural forces shape our icons, and give us the leaders we create.

Berman completely fails to understand the role of iconography in art, particularly in Catholic cultures. Che is a hero to many because he resisted a truly ugly system, remained true to his ideals, and conveniently died before the Revolution’s slow, pathetic demise became apparent to nearly everyone. He is therefore associated in the public mind with what was right about the Revolution, rather than what was very, very wrong about it … The humans underlying the icons are just stand-ins for the values they emphasize. Che has come to symbolize the values of resisting injustice and rejecting worldly excess.

The loneliest place on the left in the 1960s was reserved for those who opposed Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. …Why are people on the left so delusional about Castro and Guevara? …

One reason is Castro’s good fortune in his [American] enemies [such as ] Jesse Helms .. getting passed a law which commits the United States to side with the property claims of people who haven’t lived in Cuba in forty years.

…The second reason involves the cultural tendencies which arose in the 1960s .. …The third reason is that Fidel and Che were, in a sense, speaking to their social peers when they addressed the American left, and knew how to be heard by them.

The redress of charisma

Leadership scholars are now writing about an emerging post-charismatic view of leadership.

The dismissal of charisma as a late-twentieth century construct seems hardly likely to eliminate the idea from popular discourse, however sophisticated the objections. In practice, the term, not unlike creativity, retains some functional purpose in every-day terms. Nor can the term be defeated on the grounds that individuals labeled charismatic turn out to be narcissistic, or pathological.

The challenge seems to me to find more convincing theoretical characterizations of those behaviours that continue to be labeled as chararismatic.

We have come a long way from the idea proposed by Weber, of charisma as the revolutionary force of personality which ruptured traditional power-structures.

The term charismatic is now applied to many kinds of person. Tracing their antecedents is difficult. There seems to have been a Darwinian evolution of numerous kinds of charismatic leader to whom the term is applied.

What is overwehelmingly likely, is that no unique set of characterstics will be found that adequately captures a charismatic type. (I base this on the well-known failure of searches for univeral traits capturing the leadership construct).

It is not a coincicence, however, that the image of the charismatic is that of the idealised hero or heroine. But Don Juan was allegedly rather an ugly-looking person, and far from comely in appearance. Walt Disney, so often described as a charismatic, looks in photographs to be a quintessential salary-man. And Hitler, so easy to portray as an inadequate buffoon, nevertheless had a terrifying power over the collective that gathered to hear him.

All that being said, Che’s potency was augmented by the imposing impact of several famous images. Alexander the Great was breathtakingly handsome, and we all know the legend of Helen of Troy.

Taxonomizing charisma

This post deal with two revolutionary figures, Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. A wider examination of political and revolutionary charismatics would include advocates of non-violence: Ghandi, Mandela (well, let’s say the iconic Mandela), as well as some of the leaders classed as tyrants by Jeff Schubert.

Broadening the scope of the investigation, we would add the charismatic business leader, who at times seems associated with various power-grabbing common to alpha-males of other primate species. Then there is the more local recognition accorded to the charismatic sales manager, school teacher, tenor, civil servant, tennis coach, entrepreneur, cleric …

Maybe there is scope for a someone to develop a taxonomy of charismatic leaders, applying the methods of linguistic analysis.

Posted by Tudor Rickards

Posted by Tudor Rickards  Click for regular updates

Click for regular updates